Taoism - as lived by Pooh and Piglet

It’s important that each one of us conceive of ourselves, of all of humanity, as a species emerging from its childhood and moving toward more mutually supportive, adult behaviour. Remember, what you visualise and expect has a powerful effect upon the world you experience. Your vision will assist all of us to grow up in consciousness.

One wonders, however, if there might be some effective way to accelerate the maturation process of the nations and governments of our planet. The need is large. If we continue in the direction we are currently headed, we may well destroy much of the life of earth and make it, for our descendents, more of a trash heap than a lovely place to live.

Hopi prophecy foretold that the white people would bring the “gourd of ashes” that would create great destruction and loss of human life upon the earth. They believe that gourd of ashes refers to the atomic and nuclear bombs. Speaking to the United Nations, Hopi Elder Thomas Banyacya said, “If you, the nations of this Earth, create another great war, the Hopi believe we humans will burn ourselves to death with ashes.”

| Various American Indian tribes (Cherokee, Lakota Sioux, Hopi) have prophecies relating that when our materialistic, greedy ways have gone too far and thereby endanger the health of Mother Earth, a rainbow family or rainbow tribe would arise. This group of “Rainbow Warriors” will defend Mother Earth from the ravages to which she is being subjected. Taking up the flag of this cause, the environmental activist group, Greenpeace, named one of their ships “Rainbow Warrior”. |

|

After thousands of years of the rise and fall of philosophies and their followers, two Chinese traditions survived the test of time and are still active today, the Confucionists and the Taoists. Nowhere are they as well-described as by Benjamin Hoff in The Tao of Pooh and The Te of Piglet. Below, the story is told using extensive quotes from these two books. In classic Taoist style, Hoff uses storytelling to scathingly reveal the blunders and misuse of power by both individuals and especially by the ruling class in American and in Western society in general. And he uses Taoist principles to reveal a vision and provide practical solutions to the woes of modern civilisation. For brevity, I’ve left out many of the extremely humourous and illustrative stories, so be sure to read the original as well.

|

THE TAO OF POOH AND THE TE OF PIGLET

|

|

|

Near the beginning of The Tao of Pooh, Benjamin Hoff describes the difference between the three main philosophies of China by using a famous, often copied, work of Chinese art: The Vinegar Tasters. |

| To K’ung Fu–tse (kung FOOdsuh), life seemed rather sour. He believed that the present was out of step with the past, and that the government of man on earth was out of harmony with the Way of Heaven, the government of the universe. Therefore, he emphasised reverence for the Ancestors, as well as for the ancient rituals and ceremonies in which the emperor, as the Son of Heaven, acted as intermediary between limitless heaven and limited earth. Under Confucianism, the use of precisely measured court music, prescribed steps, actions, and phrases all added up to an extremely complex system of rituals, each used for a particular purpose at a particular time. A saying was recorded about K’ung Fu-tse: “If the mat was not straight, the Master would not sit.” This ought to give an indication of the extent to which things were carried out under Confucianism. |

Confucius |

Buddha |

To Buddha, the second figure in the painting, life on earth was bitter, filled with attachments and desires that led to suffering. The world was seen as a setter of traps, a generator of illusions, a revolving wheel of pain for all creatures. In order to find peace, the Buddhist considered it necessary to transcend “the world of dust” and reach Nirvana, literally a state of “no wind.” Although the essentially optimistic attitude of the Chinese altered Buddhism considerably after it was brought in from its native India, the devout Buddhist often saw the way to Nirvana interrupted all the same by the bitter wind of everyday existence. |

| To Lao-tse (LAOdsuh), the harmony that naturally existed between heaven and earth from the very beginning could be found by anyone at any time, but not by following the rules of the Confucianists. As he stated in his Tao Te Ching (DAO DEH JEENG), the “Tao Virtue Book,” earth was in essence a reflection of heaven, run by the same laws – not by the laws of men. These laws affected not only the spinning of distant planets, but the activities of the birds in the forest and the fish in the sea. According to Lao-tse, the more man interfered with the natural balance produced and governed by the universal laws, the further away the harmony retreated into the distance. The more forcing, the more trouble. Whether heavy or light, wet or dry, fast or slow, everything had its own nature already within it, which could not be violated without causing difficulties. When abstract and arbitrary rules were imposed from the outside, struggle was inevitable. Only then did life become sour. |

Lao-Tse |

Over the centuries Lao-tse’s classic teachings were developed and divided into philosophical, monastic, and folk religious forms. All of these could be included under the general heading of Taoism. But the basic Taoism that we are concerned with here is simply a particular way of appreciating, learning from, and working with whatever happens in everyday life. From the Taoist point of view, the natural result of this harmonious way of living is happiness. You might say that happy serenity is the most noticeable characteristic of the Taoist personality and a subtle sense of humor is apparent even in the most profound Taoist writings, such as the twenty-five-hundred-year-old Tao Te Ching. In the writings of Taoism’s second major writer, Chuang-tse (JUANGdsuh), quiet laughter seems to bubble up like water from a fountain.

|

“But what does that have to do with vinegar?” asked Pooh.

“I thought I had explained that,” I said. “I don’t think so,” said Pooh. “Well, then, I’ll explain it now” “That’s good,” said Pooh. |

“Sweet? You mean like honey?” asked Pooh.

“Well, maybe not that sweet,” I said. “That would be overdoing it a bit.”

And now from the companion book, The Te of Piglet:

… we’ll begin with a Taoist explanation of the Origin of Taoism. And we might as well stay where we are, because wherever in the world we may be at any moment is where Taoism started –whether or not it was known there by that name. It began before the time of the Great Separation.

Thousands of years ago, man lived in harmony with the rest of the natural world. Through what we would today call telepathy, he communicated with animals, plants, and other forms of life – none of which he considered “beneath” himself, only different, with different jobs to perform. He worked side by side with earth angels and nature spirits, with whom he shared responsibility for taking care of the world.

The earth’s atmosphere was very different from what it is now, with a great deal more vegetation-supporting moisture. A tremendous variety of vegetable, fruit, seed, and grain food was available. Because of such a diet, and a lack of unnatural strain, human life span was many times longer than what it is today. The killing of animals for food or “sport” was unthinkable. Man lived at peace with himself and the various life forms, whom he considered his teachers and friends.

But gradually at first, and then with increasing intensity man’s Ego began to grow and assert itself. Finally, after it had caused many unpleasant incidents, the consensus was reached that man should go out into the world alone, to learn a necessary lesson. The connections were broken.

On his own, feeling alienated from the world he had been created from, cut off from the full extent of its abundance, man was no longer happy. He began to search for the happiness he had lost. When he found something that reminded him of it, he tried to possess it and accumulate more – thereby introducing Stress into his life. But searching for lasting happiness and accumulating temporary substitutes for it brought him no satisfaction.

As he was no longer able to hear what the other forms of life were saying, he could only try to understand them through their actions, which we often misinterpreted. Because he was no longer cooperating with the earth angels and nature spirits for the good of all, but was attempting to manipulate the earth forces for his benefit alone, plants began to shrivel and die. With less vegetation to draw up and give off moisture, the planet’s atmosphere became drier, and deserts appeared. A relatively small number of plant species survived, which grew smaller and tougher with passing time. Eventually they lost the radiant colors and abundant fruit of their ancestors. Man’s life span began to shorten accordingly, and diseases appeared and spread. Because of the decreasing variety of food available to him – and his growing insensitivity – man began to kill and eat his friends, the animals. They soon learned to flee from his approach and became increasingly shy and suspicious of human motives and behavior. And so the separation grew. After several generations, few people had any idea of what life had once been like.

As man became more and more manipulative of and violent toward the earth, and as his social and spiritual world narrowed to that of the human race alone, he became more and more manipulative of and violent toward his own kind. Men began to kill and enslave each other, creating armies and empires, forcing those who looked, talked, thought, and acted differently from them to submit to what they thought was best.

Life became so miserable for the human race that, around two to three thousand years ago, perfected spirits began to be born on earth in human form, to teach the truths that had largely been forgotten. But by then humanity had grown so divided, and so insensitive to the universal laws operating in the natural world, that those truths were only partially understood.

As time passed, the teachings of the perfected spirits were changed, for what one might call political reasons, by the all-too-human organizations that inherited them. Those who came into prominence within the organizations wanted power over others. They downplayed the importance of non-human life forms and eliminated from the teachings statements claiming that those forms had souls, wisdom, and divine presence – and that the heaven they were in touch with was a state of Unity with the Divine that could be attained by anyone who put aside his ego and followed the universal laws. The power-hungry wanted their followers to believe that heaven was a place to which some people – and only people – went after death, a place that could be reached by those who had the approval of their organizations. So not even the perfected spirits were able to restore the wholeness of truth, because of interference by the human ego.

Down through the centuries, accounts of the Great Separation, and of the Golden Age that existed before it, have been passed on by the sensitive and wise. Today in the industrial West, they are classified as mere legends and myths – fantasies believed in by the credulous and unsophisticated, stories based only on imagination and emotion. Despite the fact that quite a few people have seen and communicated with earth angels and nature spirits, and that more than one spiritual community has grown luscious fruits and vegetables by cooperating with them and following their instructions, descriptions of these beings are generally dismissed as “fairy tales.” And, although colored and simplified accounts of the Great Separation can be found in the holy books of the world’s religions, it is doubtful that many followers of those religions strongly believe in them.

However, a number of pre-Separation skills, beliefs, and practices have been preserved. On the North American continent, they are passed on in some of what remains of native teachings – those of the “Indians.” In Europe they have largely died out, but traces of their influence can still be seen in such comparatively recent phenomena as stone circles and the marking of “ley lines” (called “dragon veins” by the Chinese) – channels along which earth energy is concentrated. In Tibet, until the Communist invasion, ancient ways were preserved in Tibetan Buddhism, many of the secrets and practices of which predate Buddhism by thousands of years. In Japan, they can be found in some of the rituals and beliefs of the Shinto (“spirit way”) folk religion. In China, they have been passed on through Taoism. And, despite violent opposition from China’s Communist government, they continue to be passed on today.

Briefly, Taoism is a way of living in harmony with Tao, the Way of the Universe, the character of which is revealed in the workings of the natural world. Taoism could be called either a philosophy or a religion, or neither, since in its various forms it does not match up with Western ideas or definitions of either one.

In China, Taoism is what might be called the counterbalance of Confucianism, the codified, ritualized teachings of K’ung Fu-tse, or “Master K’ung,” better known in the West as Confucius. Although Confucianism is not a religion in the Western sense, it could be said to bear a certain resemblance to puritanical Christianity in its man-centered, nature-ignoring outlook, its emphasis on rigid conformity and its authoritarian, No-Nonsense attitude toward life. Confucianism concerns itself mostly with human relations – with social and political rules and hierarchies. Its major contributions have been in the areas of government, business, clan and family relations, and ancestor reverence. Its most vital principles are Righteousness, Propriety, Benevolence, Loyalty, Good Faith, Duty, and Justice. Briefly stated, Confucianism deals with the individual’s place within the group.

In contrast, Taoism deals primarily with the individual’s relationship to the world. Taoism’s contributions have been mostly scientific, artistic, and spiritual. From Taoism came Chinese science, medicine, gardening, landscape painting, and nature poetry. Its key principles are Natural Simplicity, Effortless Action, Spontaneity, and Compassion. The most easily noticed difference between Confucianism and Taoism is emotional, a difference in feeling.

Confucianism is stern, regimented, patriarchal, often severe; Taoism is happy, gentle, childlike, and serene – like its favorite symbol, that of flowing water.

Taoism is classically viewed as the teachings of three men: Lao-tse (“Master Lao”), author of the major Taoist classic, the Tao Te Ching, which is said to have been written around twenty-five hundred years ago; Chuang-tse (“Master Chuang”), author of several works and founder of a school of writers and philosophers during the Warring States period, approximately two thousand years ago; and the semi-legendary Yellow Emperor, who ruled over forty-five hundred years ago, and to whom are attributed various meditative, alchemical, and medicinal principles and practices. These three were the great organizers and communicators of Taoist thought, rather than its founders; for, as we have said, what is now known as Taoism began before any of them were born, in what Chuang-tse called the Age of Perfect Virtue:

In the Age of Perfect Virtue, men lived among the animals and birds as members of one large family. There were no distinctions between “superior” and “inferior” to separate one man or species from another. All retained their natural Virtue and lived in the state of pure simplicity...

In the Age of Perfect Virtue, wisdom and ability were not singled out as extraordinary The wise were seen merely as higher branches on humanity’s tree, growing a little closer to the sun. People behaved correctly, without knowing that to be Righteousness and Propriety. They loved and respected each other, without calling that Benevolence. They were faithful and honest, without considering that to be Loyalty. They kept their word, without thinking of Good Faith. In their everyday conduct, they helped and employed each other, without considering Duty. They did not concern themselves with Justice, as there was no injustice. Living in harmony with themselves, each other, and the world, their actions left no trace, and so we have no physical record of their existence...

We might point out here that Taoism has always been fond of Very Small Animals. Aside from animals themselves – which Confucianists saw as mere things to eat, sacrifice, or pull plows and wagons – the Very Small Animals of traditional, Confucianist-dominated Chinese society were women, children, and the poor. Stepped on by greedy merchants, landholders, and government officials, the poor were at the very bottom of the Confucianist social scale. To put it another way, they weren’t on it at all. Women, even those of wealthy families – especially those of wealthy families – weren’t much better off, as the Confucianists practiced arranged marriage, polygamy, foot-binding (foot-breaking, actually), and other customs so repressive to women that no one in today’s West could comprehend them. Children didn’t have a very jolly time of it, either. To the staunch Confucianist, children existed to carry on the family line, unquestioningly obey their parents in every matter, and take every care of them in their old age – not to have ideas, ideals, and interests of their own. Under Confucianism, a father could justifiably kill a son who disobeyed or disgraced him, as such behavior was considered criminal.

In contrast, Taoism held that respect was something one earned, and that if Big Daddy misbehaved, his family had the right to rebel. That applied to the emperor and his “family” – his subjects – as well: If the emperor was a tyrant, the people had the right to take him off the throne. High Confucianist officials lived in constant fear of Taoist- and Buddhist-influenced secret societies that were ever ready to defend the stepped-on and attempt to topple the Dragon Throne if conditions became intolerable, which they often did.

Taoist sympathies were always with the Underdog – with the outcasts and unfortunates of Chinese society, including those financially ruined by the tricks of corrupt merchants and officials and forced to become “Brothers of the Green Woods” (outlaws) and “Guests of Rivers and Lakes” (vagabonds). The Chinese martial arts were developed primarily by Taoists and Buddhist monks, in order to defend the defenseless and enable them to defend themselves. They might better be termed the anti-martial arts, as they were employed not only against armed bandits, but also against the soldiers of warlords and governing bodies, whenever they turned their swords against the weak. While Buddhist martial artists tended to concentrate on the “hard” forms of defense (from which evolved the forceful and direct Karate and Tae Kwon Do), Taoists tended to concentrate on the “soft” forms, such as the fluid and indirect Tai Chi Ch’uan and Pa Kua Chang (similar to, but more sophisticated than Judo and Aikido).

In countering what they saw as abuse of power, Taoist writers did with their communicative skills what Taoist martial artists did with disarming moves and pressure points. Utilizing the vehicles of literary fact and fiction, they publicized the misdeeds of the powerful and ridiculed the devious, the arrogant, the pompous, and the cruel. Although annoyed Confucianists often attempted to put an end to these writings, they were generally unsuccessful, as the sympathies of the common people were against them.

Considering that High and Mighty Confucianists tended to have little respect for animals, and that they sometimes referred to the “lesser” peoples of China as “pigs” and “dogs,” it is not surprising that Taoist writers recorded many animal stories – descriptions of actual occurrences as well as imaginary tales – in which maligned creatures such as mice, snakes, and birds of prey demonstrate virtuous conduct that Prestigious People would do well to emulate. In these stories, the courage, affection, faithfulness, and honesty of animals are contrasted with the pretentiousness and hypocrisy of wealthy land-holders, merchants, and government officials. As an early example, Chuang-tse wrote:

The Officer of Prayer went to the pigpen in his official robes, and spoke to the pigs. “Why should you complain?” he asked. “I will feed you grain for three months. Then I will fast for ten days – while you eat – and keep watch over you for three days after that. Then I will spread fresh mats and place you on the carved sacrificial stand, before dispatching you to the spirit world. Considering all that I will be doing for you, why should you feel uneasy?”

If the official had been truly concerned with the welfare of the pigs, he would have fed them bran and chaff and left them alone. But he looked at the situation from the point of view of his own prestige. He preferred to enjoy the robes and cap of his privileged office, and to ride about in an ornamented carriage – knowing that when he died, he would be carried in splendor to his grave, a magnificent canopy spread above his coffin. If he had been concerned with the welfare of the pigs, he would not have considered these things to be important.

Wealthy Confucianists weren’t the only targets of Taoist writers. Like the Marx Brothers or Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, the Taoists satirized Big Ego at any level of society…

In order to understand Taoist support of the Underdog, one needs to understand the Taoist attitude toward power, from the Power of the Universe on down. As with other matters, the Taoist view was historically more or less the opposite of the Confucianist.

The Confucianist conception of Heavenly Power, vague thought it tended to be, bore a certain resemblance to the Middle Eastern, Old Testament image of God. The Confusianists called it T’ien – “Sky,” “Heaven,” or “Supreme Ruler”. T’ien was seen as masculine, sometimes ferociously so. It needed to be appeased with sacrifices and rituals. It took sides; it granted authority. It transmitted sovereignty directly to the emperor, the Son of Heaven. From him dominion spread downward and outward – from the highest officials to the lowest, from the major clans to the minor families. T’ien was imagined as dazzling in appearance (hence the brilliant colors used by the imperial family and the great clans). It was said to grant material prosperity as a reward (hence the Confucianist equation of wealth with goodness). It a word, it was considered awesome – something to fear, rather than love (hence the emphasis on unquestioning obedience to superiors, and the absence of words such as compassion from the Confucianist vocabulary). Such was the image of Heavenly Power that Confucianists presented to the common people. At the community level, it was shown in the courtroom treatment of complainants, witnesses, and the accused, not one of whom was allowed legal counsel or defense: All had to kneel on a hard floor (sometimes on chains) before the magistrate, who, as the emperor’s representative in local government, had the right to extract testimony and confessions by torture – and, since under chinese law no criminal could be sentenced until he had confessed, torture was the order of the day (hence the development of Chinese Torture). Because of centuries of this sort of intimidation, the majority of Chinese have tended to avoid whenever possible the workings of official government. Unfortunately, this Unwillingness to Openly Participate has allowed one tyrant after another – including those of the present totalitarian bureaucracy – to gain and maintain control of the nation.

| Unlike the Confucianists, Taoists saw the Power of Heaven as both masculine and feminine, as symbolized by the Taoist T’ai Chi – the circle divided by a curved line into light and dark, or male and female, halves. |

|

|

Heavenly Power at work in the natural world (according to Lao-tse) is mostly feminine in its actions. It is gentle, like flowing water. It is humble and generous, like a fertile valley, feeding all who come to it. It is hidden, subtle, and mysterious, like a landscape glimpsed through mist. It takes no sides, grants no authority. It cannot be influenced or appeased by sacrifices and rituals. In dispensing justice, as in all things, it operates with a light touch, an invisible hand. As Lao-tse put it, “Heaven’s net has wide meshes, but nothing slips through.” Shying away from displays of arrogance and egotism, it communicates its deepest secrets not to high government officials, pompous scholars, or wealthy landowners, but to penniless monks, little children, animals and the “fools.” If it can be said to be biased in any way, it is in favor of the humble, the weak, the small... |

Yes, well – Speaking of Illusions, let’s return to that subject. We believe there are a few things more to be said.

Although Illusions exist all over the world, the Industrial West seems to have more than a fair share of them. And the Illusions of the West – which of course by now have been exported to the East –deserve to be watched out for with special care. It seems rather ironic, somehow, that “realistic,” “scientific” Western industrial society sneers at the relatively harmless myths and acquired beliefs of the native peoples of the world – a good many of which have at least some basis in fact – while perpetuating irrational beliefs and practices so dangerous that they are destroying the earth. And probably the most destructive of all the Illusions of the West is the superstitious notion that Technology will solve all our difficulties.

| This Technology Worship could be said to have started in Western Europe in the 1500s or so, with Explorations and Expansions that led to the growth of Commercialism, which led to the Industrial Revolution of the 1700s. The rapid proliferation of Hungry Machines, and the accompanying break-neck exploitation of natural resources with which to feed them, quickly transformed rural, agricultural societies “Good morning, Mrs. Witherspoon! What a lovely cow!” – into city and factory societies (“I certainly hope – gasp, wheeze – we don’t run out of – cough – coal before the day is over!”) and then into big city, big industry societies: “That’s right, Inspector – they stole everything that wasn’t fastened to the floor!” In the Victorian era, this Industrial Fanaticism was given a large boost by empire-and-opinion makers who believed that science could do anything, and that any opinions to the contrary were heresy. |

|

And with it came the absurd and groundless belief that money could buy happiness. It would have been rather surprising if such a belief had not arrived on these shores, considering that a good many of the earliest immigrants were debtors from English prisons, fur trappers, tobacco and cotton barons-to-be, and Puritan tradesmen. Such people tended to know enough about the natural world to exploit it, but not much more – if indeed they knew even that. The Puritans in particular knew next to nothing about how to get along in the North American forests, meadows, and mountains, and next to nothing about how to get along with the people who did. As the old saying puts it, “They fell first upon their knees, and then upon the Indians.” And then upon the landscape. As Luther Standing Bear, chief of the Oglala Sioux, described the situation:

Luther Standing Bear |

We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth, as “wild.” Only to the white man was nature a “wilderness” and only to him was the land “infested” with “wild” animals and “savage” people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it “wild” for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was that for us the “Wild West” began. |

In truth, Western industrial society does not even notice the Material World. It quickly discards it, leaves it to rust in the rain. The material world is Here and Now, and industrial society does not appreciate or pay attention to the Here and Now. It’s too busy coveting and rushing after the There and Later On.

As a result, it all too often fails to see what is right in front of it, and what’s coming from that. It forgets where it has been; it does not know where it is going.

Perhaps the preceding glimpse at our historical conditioning can help to explain why Western industrial society has such a poor record when it comes to observing What’s There. In our part of the world, this unobservant tendency is displayed in the most depressing manner whenever there’s an Election. For nearly thirty years now, the nation that was once the Light of the Free World has been electing to the highest office in the land a succession of Nightmare Clowns who lead us deeper and deeper into darkness as they encourage massive greed and corruption, run up multibillion-dollar debts for future generations to pay turn the economy into jelly, refuse to take action necessary to save what’s left of the natural world (“More studies are needed”), and threaten to blow up the planet because some country somewhere isn’t doing what they think it ought to quickly enough – all the while making remarks on the intelligence level of “If you’ve seen one redwood tree, you’ve seen them all.”

And speaking of trees, if the majority of voters are not living in some sort of fantasy, why this increasing tendency to talk about Protecting the Environment while voting more than ever against it? In a recent election in our once-almost- environmentalist home state (Oregon), for example, the majority voted to allow one of the nation’s most notoriously unsafe and unnecessary nuclear power plants to continue operation despite its persistent violation of vital safety regulations; rejected a measure that would have restricted throwaway packaging; and turned down an honest, self-funded, pro-environment political candidate to re-elect a politician who for years has actively opposed the preservation of what little remains of the state’s uncut forests, who supports the timber industry’s policy of clearcutting public lands and sending the logs overseas for processing (thereby shutting down local mills), and who has annually appended to appropriations bills riders forbidding citizens from challenging this policy in court. So much for Planet Earth.

The natural world is all right, voters across the country seem to be saying, as long as its preservation doesn’t interfere with the process of destroying it to earn money. Let Someone Else pay for its protection. But, considering that less than 1 percent of American philanthropic giving goes to conservation, it would appear that Someone Else is just another fantasy.

|

Unfortunately for our chances of survival and happiness, we in the West have inherited an Eeyore version of religion, which denounces the world as an evil place whose ways are to be ignored by the wise, and an Eeyore sort of science, which sneers at anything beyond a mechanistic view of the earth – the secrets of which it attempts to sneak out of it bit by bit, for the purpose of manipulating the natural world. Is either of these Ways very likely to get us out of the mess we’re in? Or to even help us see what’s causing it? |

|

|

Eeyore science, on the other hand, insists that Technology will rescue us from destruction – including the considerable destruction that Technology causes. When it tells us things like that, we can’t help but wonder if it isn’t trying to be some sort of religion itself. No, not a religion, exactly – some sort of voodoo. |

The fearful fantasies we have inherited have conditioned us to believe that we need to be protected from the natural world. Better Living Through Heavy Industry, and so on. In reality, as anyone ought to be able to see by now, the natural world needs to be protected from us. Its wisdom needs to be recognized, respected, and understood by us, and not merely viewed through the distorted lenses of our illusions about it.

| As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle cautioned, through his character Sherlock Holmes, “One’s ideas must be as broad as Nature if they are to interpret Nature,” and “When one tries to rise above Nature one is liable to fall below it.” Chuang-tse’s words to that effect have a timely ring: “When leaders pursue knowledge but do not follow the Way, all who follow them become lost in confusion… Much knowledge is utilised in the design and placement of traps, meshes, and snares, but the creatures of the ground are disturbed and injured by it. As knowledge becomes increasingly clever, versatile, and artful, the people all around are disturbed and injured by it. They then struggle to grasp what they do not know, but make no attempt to grasp what they know already. They condemn the misunderstanding of others, but do not condemn their own. From this more confusion comes… This is the condition produced in men by an obsession for knowledge. Honesty and simplicity are over-looked, and restlessness is admired. Quiet, effortless action is forgotten, and loud quarreling is heard. Such is the nature of hunger for knowledge. Its noise throws the world into chaos.” |

Sherlock Holmes |

Symbol of the Tao |

Out of the “Hundred Schools” of Chinese philosophy, only two – Confucianism and Taoism – have survived. They have lasted through thousands of years because they have proven the most Useful. The Chinese are very practical people – they have no respect for things that sound good but don’t work. In the East generally, and in China especially, philosophy has always been considered of no value unless it can be, and is, applied in one’s daily life. |

Confucius |

Looking askance at all this, the typical Mind of the West says: So who needs Eastern philosophy? To such a mind, Eastern philosophy has two things wrong with it. First, it’s Eastern – exotic and mystical, quaint but useless. Second, it’s Philosophy – And what good does that do anybody?

What this narrow-minded attitude overlooks is the fact that much of what makes up the Practical West came from the East, and most of that came from China. And, we might add, a good deal of it came from the Taoists – China’s foremost scientists, inventors, medical men, artists, and observers of the natural world.

In the West we are told in school that Johann Gutenberg invented movable type, William Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood, and Sir Isaac Newton was the originator of his First Law of Motion. In reality, these things were invented and discovered in China long before those men were born. In addition to who-knows-how-many other things, the Chinese have given the world the mechanical clock, paper (including wall-paper, toilet paper, paper handkerchiefs, money, and playing cards), multicolor printing, porcelain, lacquer, phosphorescent paint, the magic lantern (ancestor of the movie projector), the spinning wheel, the wheelbarrow, the umbrella, the modern plow, harness, seed drill, and rotary winnowing fan (as well as the practice of growing crops in rows), the fishing reel, the modern compass (and the difference between true and magnetic north), the seismograph, relief and grid maps, the decimal system, the calculator, the hermetically sealed research laboratory, the chain drive, the belt drive, the chain pump, the essentials of the steam engine, dial and pointer devices, cast iron, the manufacture of steel from cast iron, the suspension bridge, the segmental arch (nonsemi-circle) bridge, the contour transport canal, the canal pound-lock, masts, sails, the rudder, watertight compartments in ships, the paddle-wheel boat, land sailing, the kite (including the acrobatic kite, the fighter kite, the message kite, the musical kite, the lighted kite...), the hang glider (which, like the acrobatic kite, was developed and flown by Taoist adepts in the mountains of China as a way to learn and work with natural laws), the hot-air balloon, the helicopter rotor, the parachute (fifteen hundred years before Leonardo da Vinci’s), tuned bells, “church” (court and temple) bells, equal temperament in music (championed one hundred and thirty-eight years later in the West by Johann Sebastian Bach), drilling for natural gas, the butane gas cylinder (in its original form, a gas-filled bamboo tube with a valve at one end, over which travelers cooked their food on journeys), sunglasses, waterproof clothing, mountain-climbing gear, and gunpowder (which, ironically, was discovered by a Taoist searching for the formula to an elixir of longevity). A group of court ladies invented matches, which were brought to Europe one thousand years later. Some other Chinese discovered the structure of snowflakes – two thousand years ahead of the West – and the existence of sunspots and solar wind. The Chinese discovered diabetes and deficiency diseases and pioneered the sciences of endocrinology, immunology, thyroid hormone therapy, and anatomy (deducing, among other things, the presence and design of the eardrum before its physical discovery). They developed systems of biological pest control... Well, that ought to be enough to make the point. These people Noticed things.

Unfortunately, one thing the West did not import from the East was the traditional Chinese belief that science, morality, and spirituality must go together; that science without ethical and spiritual considerations was not a whole science, but a form of madness. Oh, well – we can’t have everything, we suppose.

| Returning to Pooh and friends, this business of scientific observation and so on reminds us of the quite Taoist discovery of the principle of Poohsticks, a game that has been played around the world ever since it was described in The House at Pooh Corner (and just possibly before). Pooh, as you may remember, had been studying fir-cones and had made up a rhyme about one in particular... |

|

“Bother,” said Pooh, as it floated slowly under the bridge, and he went back to get another fir-cone which had a rhyme to it. But then he thought that he would just look at the river instead, because it was a peaceful sort of day, so he lay down and looked at it, and it slipped slowly away beneath him ... and suddenly, there was his fir-cone slipping away too.

“That’s funny,” said Pooh. “I dropped it on the other side” said Pooh, “and it came out on this side! I wonder if it would do it again?” And he went back for some more fir-cones.

It did. It kept on doing it. Then he dropped two in at once, and leant over the bridge to see which of them would come out first; and one of them did; but as they were both the same size, he didn’t know if it was the one which he wanted to win, or the other one. So the next time he dropped one big one and one little one, and the big one came out first, which was what he had said it would do, and the little one came out last, which was what he had said it would do, so he had won twice ... and when he went home for tea, he had won thirty-six and lost twenty-eight, which meant that he was – that he had – well, you take twenty-eight from thirty-six, and that’s what he was. Instead of the other way around.

And that was the beginning of the game called Poohsticks, which Pooh invented, and which he and his friends used to play on the edge of the Forest. But they played with sticks instead of fir-cones, because they were easier to mark.

In that Poohishly humble incident, one can see all the elements of pure science as practiced by the Taoists: the chance occurrence, the observant and inquisitive mind, deduction of the principles involved, application of those principles, modification of materials, and a new practice or way of doing things. Not bad. But after all, Pooh is That sort of Bear.

As we have already implied, there is a good deal more to the Importance of Observation than scientific discoveries. There is also the matter of Living Wisely and Well. In this area in particular, we believe, the West could learn a few things from the East. For example, what sort of education in Practical Wisdom do we tend to receive in school?

There are three hundred cows in a field. The gate has been left open, and two cows pass through it every minute. How many cows are left in the field after an hour and a half?

This sort of thing, we’re told, will help us once we graduate – help us apply our learning to everyday matters and, ideally, help us discern the true from the false. But, to return to the terms of the threehundredcow math problem: If you have ever herded cattle, you know that cows do not pass through an open gate at the rate of two per minute. They either go through all at once, or not at all. Or they wander through whenever they feel up to it. In all probability, there would be no cows left in the field ten minutes after a gate was opened, or a fence pulled down. But if you told the teacher that, you would be told that you were wrong. Such is the difference between School and Life. (And if you in school don’t believe that such a difference exists, just wait until you get out.)

If we were asked to condense Taoist teachings regarding everyday life to their irreducible essentials, we would say: Observe, Deduce, and Apply. Watch what is around you – putting aside, as best you can, previous conceptions that you or others might have about it. Ideally, look at it as though you were seeing it for the first time. Mentally reduce it to its basic elements – “See simplicity in complexity,” as Lao-tse put it. Use intuition as well as logic in order to understand what you see (a vital difference between the Whole Reasoner and the Left-Brain Technician). Look for connections between one thing and another – notice patterns and relationships. Study the natural laws you see operating through them. Then work with those laws, applying the smallest possible amount of interference and effort, in order to learn more and achieve whatever you need to – and no more.

Once you make a habit of Observing, Deducing and Applying, you may sense a pathway opening up ahead of you – or inside of you, or both – leading to a deeper understanding of things. You may even feel at times as though you’re in some sort of Other Dimension, like Thoreau’s example of the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. But you’re not, really; you’re just seeing and experiencing Things As They Are, rather than as Someone-or-other says they are. And the difference between the two can be considerable.

In a sense, though, the image of another dimension is an appropriate one. For as you follow the Way, you leave the land of Either/Or and enter the land of Both. As Lao-tse wrote in the first chapter of the Tao Te Ching, many people are unable to follow the Way because they are unable to see it, being stuck in Either/Or:

Those habitually without desires

Perceive [the Way] as “subtlety.”

Those habitually with desires

Perceive it as “action.”

These two have the same source,

But different names.

Together they’re called “darkness” –

Darkness of increasing darkness,

All mystery’s gateway.

In other words, Tao is both “subtlety” and “action.” Those who consider it only as spirit and ignore its forms, or who notice its forms but disregard what is behind and within them, know of only half of it, at best – neither the Spiritual people who deny the world nor the Physical people who deny the spirit can know of and follow the Way. But you can.

“I feel dizzy” said Piglet, who had been reading over my shoulder.

“Yes, I did get a bit carried away, didn’t I?”

“Isn’t there some other way of explaining all that?”

“I suppose. Let’s try it like this...”

Taoism is not the reject-the-physical-world way of living that some scholars (and a few Taoists) would have others believe. Even Lao-tse, the most reclusive of Taoist writers, wrote, “Honor all under heaven as your body.” To a Taoist, a reject-the-physical-world approach would be an extremist absurdity, impossible to live without dying. Instead, a Taoist might say:

Carefully observe the natural laws in operation in the world around you, and live by them. From following them, you will learn the morality of modesty, moderation, compassion, and consideration (not just one society’s rules and regulations), the wisdom of seeing things as they are (not of merely collecting “facts” about them), and the happiness of being in harmony with the Way (which has nothing to do with self-righteous “spiritual” obsessions and fanaticism). And you will live lightly, Spontaneously, and effortlessly.

|

“Well, Piglet?” “Could you tell some stories?” “Yes, I suppose I could.” “Stories?” said Pooh, opening his eyes. “I would like to hear some stories,” said Piglet. “So would I,” said Pooh. “All seriousness aside.” “All ... Yes. All seriousness aside. Let’s see – we were just mentioning observation, spontaneity, and effortlessness .. . Would you like to hear ‘The Old Master and the Horse’?” “We won’t know,” said Pooh, “until we’ve heard it.” “True enough. This is how it goes...” |

The crowd watched eagerly as the Old Master came around the corner, saw the horse, turned, and walked down another street.

“You see” I said, “the Old Master lived the principle of Wu Wei, or Effortless Action. That’s something the Taoists say we can learn by watching water.”

“Water?” asked Piglet.

“When a stream comes to some stones in its path, it doesn’t struggle to remove them, or fight against them, or think about them. It just goes around them. And as it does, it sings. Water responds to What’s There with effortless action.”

“I think I missed something”, said Pooh.

“Missed something where?” I asked.

“In the story –”

“Oh, that. The Old Master knew he didn’t have to go down that street. He knew he could go another way.”

“But why didn’t the others know?”

“Ah! Precisely. Why didn’t they know?”

“I wouldn’t have gone down that street,” squeaked Piglet. “Not with a horse in the way. Or a goat. Or a dog. Or anything.”

“But why didn’t the others…”

“My dear Pooh”, said Owl, flying over to the writing table. “In problems of this sort, one must consider the Physical Properties involved.”

“I didn’t know there were any” replied Pooh, rubbing his ear.

“That is to say,” continued Owl, somewhat annoyed, “the street in question was narrow, the horse was large – and furthermore it was Belligerent.”

“Further along it was what?”

“It kicked. The Old Master knew that it was Futile to Proceed “

“We know that, Owl,” I said. “The point is…”

Oh, well – so much for stories. Let’s go on to the next principle.

When you observe the natural world, you’ll eventually see that everything in it is designed to succeed – including what some might judge to be “bad.” If you want to learn the natural world’s principles of success, you’ll need to see things not as “good” or “bad,” but as they are. This does not mean discard morality or common sense, or anything of the sort; it simply means – well, let’s show what it means by a couple of examples.

|

Many centuries ago, the Chinese empress Si Ling-chi overheard complaints that “worms,” or moth larvae, were devouring the leaves of the royal mulberry tree. So she went out to see what was happening. She watched the larvae as they spun their cocoons of strong, shimmering threads. Observing their movements as they spun, she conceived of a way to extract the fibers and weave clothing material from them. Her observations and experiments led to the cultivation of what was to become the most highly treasured of all the world's natural fibers – the magical material known as silk... |

|

|

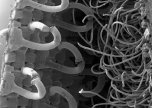

On returning from a walk about forty years ago, the Swiss engineer George de Mestral found cockle-burs clinging to his clothing. Unlike countless other people who have cursed the prickly seedpods, picked them off, and discarded them, he asked himself, “Why do they stick?” |

| Examining them closely, he found that they were covered with tiny hooks, which had become embedded in the loops of his clothing fabric. He wondered if it would be possible to develop fasteners based on a hook-and-loop principle, which would by their nature be more flexible than anything then being used. From his watching and wondering came Vel-cro – from “velvet crochet;” or “velvet hook” – fastening systems made from which are now used all over the world, in applications too numerous to mention. |

Velcro |

| The telescope, for example, was invented in principle by some Dutch children playing with defective lenses discarded from the shop of a spectacles maker. They found that when the lenses were held one in front of another – which, of course, everyone knew was not supposed to be done – distant objects appeared closer. News of their discovery spread to Italy and to the eager attention of a man named Galileo Galilei. |

Galileo |

|

For example, when a Bear overeats a bit and gets stuck in your front door... |

|

– you can use his legs to hang the washing on. And then use the back door. |

|

Most major difficulties are caused by a failure to observe the minor difficulties that they start out as. “Trouble is easily stopped before it commences,” wrote Lao-tse. “Put things in order before chaos occurs.” In other words, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of pesticide. The overwhelming tendency in unobservant industrial society, however, is to ignore small problems until they become enormous – and then panic.

“Call out the troops! Mad Tyrant Number Twelve is taking over the world! We’ve got to stop him – even we have to kill half a million people doing it! Oh, it’s simply awful.” Well, let’s see... Who sold him his weaponry? We did. Who trained his military forces in the use of it? We did. Who supplied the materials he wanted? We did. Who supported his vicious dictatorship for years because he persecuted our “enemies”? We did. And who ignored his unstable personality, his destruction of anyone who opposed him, and his repeated threats against world order for all that time? We did. So there you are.

What can be just as hard to see as problems-in-the-making is that a good many “problems” aren’t really problems to begin with. People who don’t see situations for what they are often struggle against difficulties that aren’t there and create difficulties in the process. Or turn small difficulties into large ones.

Compounding any problem (or nonproblem) is the traditional Western response to difficulties real or imagined: the tendency to see them emotionally, perceiving them as threats to one’s personal survival – threats that must be fought tooth-and-nail to the bitter end. In the East, such an approach to life is considered rather immature. Overdoing it, you know; wasting energy. Or, as the Chinese saying puts it, “Painting legs on the snake.”

So in solving problems, one needs to know if they are problems. Is what appears at first to be bad truly bad? The following selected Taoist writings show the importance of that question. The first is our streamlined version of a story from the classic Huai-nan-tse:

An old man and his son lived in an abandoned fortress on the side of a hill. Their only possession of value was a horse.

One day, the horse ran away The neighbors came by to offer sympathy “That’s really bad!” they said. “How do you know?” asked the old man.

The next day the horse returned, bringing with it several wild horses. The old man and his son shut them all inside the gate. The neighbors hurried over. “That’s really good!” they said. “How do you know?” asked the old man.

The following day, the son tried riding one of the wild horses, fell off, and broke his leg. The neighbors came around as soon as they heard the news. “That’s really bad!” they said. “How do you know?” asked the old man.

The day after that, the army came through, forcing the local young men into service to fight a faraway battle against the northern barbarians. Many of them would never return. But the son couldn’t go, because he’d broken his leg.

Is “good” necessarily good? Is “bad” necessarily bad? It’s considered good to be beautiful, but many people through being beautiful have ruined their lives and the lives of others. It’s considered bad to be unattractive, but because of being unattractive, many have come to concern themselves with matters more important than surface appearance and have gone on to make something Special of themselves – in quite a few cases becoming Beautiful in the process. It’s considered good to be healthy and strong, but many energetic people lose their health and strength by taking what they have for granted, not knowing what it’s like to be old and depleted – and therefore not taking care of themselves – until it’s Too Late. It’s considered bad to be ill and weak, but many have responded to such conditions by examining their lives and changing their ways of doing things thereby building up their health and strength to remarkable degrees. Unattractiveness, illness, and weakness have many valuable lessons to teach to those willing to learn from them.

It’s considered good to live a long life, but many spend their long lives sitting and complaining, watching television, describing their operations, and retelling for the umpteenth time what Aunt Gertrude said forty years ago. Many Great Achievers died young, yet lived every minute of the time they had. As Chuang-tse pointed out, even death itself may not necessarily be bad.

How do we know that to cling to life is not an error? Perhaps our fear of its end approaching is like forgetting our way and not knowing how to return home.

Li Chi was a daughter of the border chieftain Ai Feng. When Duke Hsien claimed her as his wife, she cried until her sleeves were soaked with tears. But after she had come to know the duke and had shared his palace, she laughed at her former fears and sadness. How do we know that the spirits of the dead do not do the same?

Those who dream of feasting may awaken to hunger and sorrow. Those who dream of hunger may, when they awaken, rise and join a hunting party. While they were asleep, they did not realize that they were dreaming... But when they awoke, they knew. Someday will come a great awakening, when we will know this life was like a dream.

These words may seem strange, but many years from now we might meet someone who can explain them, unexpectedly some morning or evening.

In the meantime, we can look clearly at our lives and the life around us, and Live. Before we start crying and praying to the Universe to take away our Trials and Tribulations, we might more closely examine what it has given us. Maybe the “good” things are tests, possibly rather difficult ones at that, and the “bad” things are gifts to help us grow: problems to solve, situations to learn to avoid, habits to change, conditions to accept, lessons to learn, things to transform – all opportunities to find Wisdom, Happiness, and Truth. To quote William Blake:

It is right it should be so;

Man was made for Joy and Woe;

And when this we rightly know,

Thro’ the World we safely go.

Joy and Woe are woven fine,

A Clothing for the soul divine.

|

“I’m still here;” said Piglet. “Oh – so you are.” “I enjoyed the stories.” “That’s good:” “They helped me to – reflect on things.” “Things?” Such as “Fear.” “Well, I’m going out on a walk, to do some thinking. I’ll be back in a bit.” “Right you are. Have a pleasant time.” |

|

What is a course of history or philosophy, or poetry, no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking always at what is to be seen? Will you be a reader, a student merely, or a seer? Read your fate, see what is before you, and walk on into futurity.

What was I about to say? Oh, yes. Now we come to the power of the Sensitive, the Modest, and the Small – a power that all Piglets have in potential, whether or not they do anything with it. Of all the teachings of East or West, Taoism places the greatest emphasis on that power, which in Taoist writings is personified in its varying aspects as the Child, the Mysterious Female, and the Spirit of the Valley. Significantly, these are also personifications of the Tao itself.

Let’s begin our examination of the Sensitive, the Modest, and the Small by considering Sensitivity. In the West, sensitivity is considered a Minus rather than a Plus. (“Oh, you’re just too sensitive!”) But even in denouncing it as something to get rid of, the West acknowledges a little of its tremendous power. For example, it is widely recognized that being negatively sensitive about one’s health through worry-imagery and pessimistic self-talk can make and keep one sick. What is not so widely recognized, however, is that being positively sensitive about one’s health – “listening” to the body, avoiding damaging influences, imagining and directing healing energy, visualizing perfect health, and so on – can make and keep one well, as an increasing number of people are discovering, some of them through curing themselves of “incurable” illnesses.

Sensitivity and skill develop together – as one of them increases in the process of learning something, so does the other. A skilled ballet dancer is aware of his muscles as they stretch and contract, tighten and relax, through exercise, practice, and performance. Applying that sensitivity, he leaps, twirls and lands without apparent effort. A skilled athlete of any sort is aware of just how to move, how to hit or throw a ball in the right way at the right time, how to do this or that in order to score a point.

|

Our last T’ai Chi Chuan teacher had developed his awareness to such an extent that he would immediately know when anyone was trying to sneak up behind him. In their areas, at least, the masters of any such skills are very sensitive – and therefore very alert.

|

“Those of perfect Virtue cannot be burned by fire, nor drowned by water. Neither can they be harmed by heat or cold, nor injured by wild animals. It is not that they are indifferent – it is that they discriminate between where they may safely rest and where they will be in danger. Watchful in prosperity and adversity, cautious in their comings and goings, nothing can injure them...”

The word for Taoist sensitivity is Cooperate. As Lao-tse wrote, “The skilled walker leaves no tracks” – he is sensitive to (and therefore respectful toward) his surroundings and works with the natural laws that govern them. Like a chameleon, he blends in with What’s There. And he does this through the awareness that comes from reducing the Ego to nothing...

To the typical mind of the West, Bigger is Better: The large man is a better fighter than the little man, the huge corporation is superior to the small company, the adult is wiser than the child. The Taoist attitude is: Not so.

Is the large man a better fighter than the little man? Our previously mentioned T’ai Chi Chuan teacher, a small man even by Chinese standards, was once trapped in a Hong Kong alley by a gang of armed thugs. They lost. In martial arts, as in Real Life, it’s not the big opponent one needs to watch out for; it’s the little one. There are many reasons, some physical (lower center of gravity), some mental (tricks learned from being the Underdog), some emotional (without interference from a Muscleman Ego, one can move very fast). Large men tend to be lazy and slow, relying on their muscles to carry them through a situation. Little men tend to be far more energetic, flexible, and alert, with finer-tuned nervous systems and less weight to haul around. We’ve so often seen small fighters dance around their larger opponents, strike them at will and dance out of range, that we laugh when we’re told what a Big Bruiser so-and-so is. What does it matter if he’s as big as a boxcar, if he can’t catch you?

|

For the second point: Is the huge corporation superior to the small company? That sort of Dinosaur Mentality didn’t work very well for the dinosaurs in the long run, and it doesn’t seem to be working very well for businesses, either, as time goes by. |

|

For some time now, big companies have been buying smaller companies, only to be bought in turn by giant corporations, which are then bought by multinational conglomerates. The bigger they grow, and the more interdependent they make themselves in the process, the more vulnerable they become. Bigness easily becomes its own worst enemy As recent events continue to show, it doesn’t take all that much to put a large corporation in trouble. And the bigger it is, the harder it will fall. Survival of the Fattest may have been the rule of business prosperity for a while. But it’s now being supplanted by the Success of the Small. In search of something new and useful, creative businessmen have begun to study the fighting tactics of the Samurai. They might do better, we think, to read the Tao Te Ching: “The hard and mighty shall fall; the flexible and yielding shall survive.” Just a thought...

For the final point on Bigger is Better: Is the adult wiser than the child? On the individual level, of course, the answer depends on which adult and which child. But beyond that, wisdom is to the Taoist a child’s state. Children are born with it; most adults have lost it, or a good deal of it. And those who haven’t are, in one way or another, like children. Is it a Mere Coincidence that the Chinese suffix tse, which has come to mean “master,” literally means child? As the Confucianist-yet-surprisingly-Taoist philosopher Meng-tse wrote, “Great man retains child’s mind.”

|

Piglet composes a song: There’s not much you can see When you can’t see things at all – They’re too far above your head. They’re for someone Who is Someone, Not for someone who is like you – How can I become Bigger? How can I become Tall? When will I stop feeling weak, and When will I stop feeling small? |

|

“What do you mean?” asked Piglet.

“I mean, that attitude won’t do you any good. If you keep repeating that sort of thought, you’ll just convince yourself that you’re powerless. Isn’t that why you feel so afraid?”

“Well,” said Piglet, “when you’re only a Very Small Animal...”

“If I might make a suggestion?”

“Yes?”

“First of all, the fears that push you about are not legitimate, appropriate responses to What Is, such as warnings of danger ahead. Instead, they’re the constricting fantasies of What If ‘What if I should is like you meet a Heffalump, or fall on my face, or make an utter fool of myself?’ Isn’t that true?”

“Yes – I suppose so.”

“I would suggest that the next time a What If starts badgering you, look it straight in the eyes and ask it, ‘All right, what's the very worst that could happen?’ And when it answers, ask yourself, ‘What could I do about it?’ You’ll find there always will be something. Then you’ll see that you can have power in any situation. And when you realize that, the fears will go away.”

“They will?”

“Especially when you realize where the power comes from. In one way or another, we’re all Very Small Animals, and that’s all we need to be. So why worry about it? All we have to do is live in harmony with the Way, for the benefit of the world, and let its power work through us. Let it do the work.”

“Oh,” said Piglet.

“For example, I’m not writing this book. That would be Struggle and Difficulty. Instead, I’m letting the book write itself, through me. That’s Fun and Excitement. It flows along, and I follow as best I can. Day by day, wherever I go, things come to me and I include them in these pages. To paraphrase my favorite Haiku writer, Matsuo Bash ‘Every bend in the road brings me new ideas; every dawn gives me fresh feelings. Writing with the Way is a journey. And so is everything else. Who knows where the Way will take us tomorrow, and what it will have us doing?’”

“I never thought of it like that,” said Piglet.

“So you see, as long as we follow the Way, we won’t be intimidated by fears – neither fear of failure nor fear of success...”

It’s intriguing, and rather Eerie sometimes, how history tends to repeat itself. To Us First, War Lord Confucianists criticized by Lao-tse and other ancient taoists seem to have put on new clothes can come back to take charge. Reading the Tao Te Ching’s descriptions of the society of its time, one gets the strangest feeling that they were written the day before yesterday. So once again, Taoism – for all its great age – seems very up-to-the-minute. And once again, perhaps it has something to offer.

John F. Kennedy |

Because, we believe, it is not exactly Progress for our nation to have moved from the enlightened era of President John F. Kennedy (was it the Merest Accident that he quoted occasionally from the Tao Te Ching?) into an era of scandal-ridden administrations run by Special Interests’ Candidates seemingly bent on dismantling our democracy and destroying the nation’s land, air, and water in the process, while wrapping themselves in the starry flag of Patriotism. For years now, intelligent, concerned activists have been Out, and self-centered, ignoramus conservatives have been In. And that is not what we’d call the Way of a Healthy Society. |

The Conservatives (being very religious people, they say) believe that “God helps those who help themselves.” And so they help themselves to everything they can get their hands on. But don’t expect them to help anyone else. And don’t expect them to help the earth.

ln recent years, for example, our nation’s “conservative” leaders have started a war to take Kuwait’s oil supply back from Iraq, waging that war by authorizing the bombing of offshore oil rigs (contributing to the largest oil spill in history), goading the opposing forces into igniting 30 percent of Kuwait’s oil wells, killing a quarter of a million people (many of them civilians far from any military targets) in what is now known as the most environmentally destructive war in the history of warfare. The bill: sixty billion dollars. They have trashed the energy conservation measures of their predecessors – all but eliminated funding for solar energy research and development, handed the wealthy nuclear power industry a taxpayer-funded boost, pressed for oil drilling in wildlife refuges and coastal waters, refused to authorize the long-overdue and increasingly costly cleanup of toxic waste sites, and so on, and on and on. With wasteful, destructive “leaders” such as these, who needs enemies?

Unfortunately for those of us who would prefer to go on to bigger and better things – such as the advancement of humanity and the assurance of its survival – the great majority of political leaders now in power seem to care for nobody but themselves. And, as in days of old, that means War.

At present, billions of American tax dollars are being spent each year on preparations for war, weapons of war, industries of war – running the nation into unpayable debt while across the country untaxed gang lords cruise about in limousines, drug pushers and psychopaths prey on neglected children, homeless grandmothers push their worldly possessions before them through the streets in shopping carts, and citizens of all ages contract Pistol Fever, shooting themselves and each other with handguns at the rate of sixty-four deaths per day – killing more Americans in two-and-one-half years than did the sixteen-year Vietnam War (and wounding approximately one hundred thousand others yearly).

The huge-like-us Soviet Union went Broke feeding the military, and we’re following Close behind. Meanwhile, little Germany and little Japan, who comparatively speaking spend next to nothing on military matters, are beating us in practically every area of endeavor. What do we receive in return for the trillions of dollars that we’ve handed to the Armed Forces over the past thirty years? Let’s see.

Well, we’ve been provided with warplanes that don’t fly; armored tanks that don’t steer; weapons that don’t fire ... No, those don’t count. That’s what we're told, anyway. Oh, there must be something... Ah, yes – half a million tons of hazardous waste per year. The military is the nation’s largest producer of it. What good that will do us is rather hard to say, however. And toxic waste isn’t exactly the sort of thing we can return to the store for a refund.

Of course, that waste is sooner or later bound to leak out. Fourteen thousand four hundred military sites are now officially recognized as toxin contaminated – the cleanup of which is expected to cost taxpayers over two hundred billion dollars – making the U.S. military the country’s leading Earth Abuser. The military now directly manages about twenty-five million acres of public land and “borrows” around eight million more from agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service – which allows one hundred sixty-three military training activities in fifty-seven national forests, involving three million acres. How respectfully do the Armed Forces treat the land they manage? Well...

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers describes Basin F of Colorado’s Rocky Mountain Arsenal as “the most contaminated square mile on earth.” Thousands of animals and birds have died by drinking or landing in its water. Nevada’s “Bravo 20” range is a sixty-four-square-mile moonscape after fifty years of battering. In 1983-1984, water from Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge overflowed into the area and mixed with the chemicals in its bomb craters, then receded back into the refuge – killing seven million fish and thousands of birds. Twenty-three million artillery, tank, and mortar shells have blasted the forests and meadows of Indiana’s ninety-square-mile Jefferson Proving Ground. Approximately one-and-one-half million of these rounds have not yet exploded. Many are below the surface, nearly impossible to locate. An expert has stated that to decontaminate the once-unspoiled area, it would be necessary to remove thirty feet of ground using armored bull-dozers – thirty feet down for ninety square miles.

“When the empire follows the Way” wrote Lao-tse, “horses haul wagons of fertilizer through the fields. When the empire loses the Way, horses haul war chariots beyond the city walls.” And:

I have three treasures,

Which I guard and keep.

The first is compassion.

The second is economy.

The third is humility.

From compassion comes courage.

From economy comes the means to be generous.

From humility comes responsible leadership.

Today, men have discarded compassion

In order to be bold.

They have abandoned economy

In order to be big spenders.

They have rejected humility

In order to be first.

This is the road to death.

The Taoist ideal is to rule by “filling stomachs and building bones” – to take care of society from the bottom up. Today’s leaders in government, business, and industry “take care of society” by giving more and more money and power to those at the top. And the Buck Stops There. As Lao-tse described the situation:

The court is filled with splendor.

The fields are full of weeds.

The granaries are empty.

The powerful wear costly clothing,

Carry sharp swords,

Pamper themselves with lavish food and drink,

And possess riches in extravagance.

These are not princes and lords.

They are robber barons.

|

Pooh had found Piglet, and they were walking back to the Hundred Acre Wood together. “Piglet,” said Pooh a little shyly, after they had walked for some time without saying anything. |

|

“Do you remember when I said that a Respectful Pooh Song might be written about You Know What?”

“Did you, Pooh?” said Piglet, getting a little pink round the nose. “Oh, yes, I believe you did.”

“You don’t often get seven verses in a Hum, do you, Pooh?”

“Never” said Pooh. “I don’t suppose it’s ever been heard of before.”

“Do the Others know yet?” asked Piglet, stopping for a moment to pick up a stick and throw it away.

“No,” said Pooh. “And I wondered which you would like best. For me to hum it now, or to wait till we find the others, and then hum it to all of you.”

|

Piglet thought for a little. “I think what I’d like best, Pooh, is I’d like you to hum it to me now – and – and then to hum it to all of us. Because then Everybody would hear it, but I could say ‘Oh, yes, Pooh’s told me,’ and pretend not to be listening.” |

Yes, we have our doubts about how much love this country truly has for the earth. Doesn’t such love begin at home? Yet even a quick glance inside the typical American house and garage would reveal a startling number of anti-earth chemical weapons with which to keep the forces of the natural world at bay. And outside . . . Americans dump sixty-seven million pounds of pesticide onto the nation’s lawns each year – more than farmers use to grow the nation’s pesticide-laden food. Some of the thirty-four chemicals used in these Lawn Wonders have not been government tested since the 1940s. And the rest may not be particularly safe, either...

If we appear a bit Hesitant to embrace the belief that we can go on behaving in such an irresponsible manner without paying the inevitable price, perhaps it’s because we live on a planet on which five to ten species of life are driven to extinction every day, over seventy-five acres of trees are cut every minute, one third of the land area has become desert, and life-threatening droughts and floods are becoming increasingly common year after year. In Southern Chile, under the emissions-caused hole in the earth’s ozone layer – which is four times larger than the United States, and growing – dark glasses, hats, and full clothing in midsummer are becoming common-place as carcinogenic ultraviolet-B radiation jumps to an estimated 1,000 percent of the pre-hole amount on peak days. In the same area rabbits, sheep, and fish blinded by apparently ultraviolet-ray-induced cataracts are being found in ever-larger numbers.

And so when we hear Big Talk about growing environmental awareness and about man’s ability to solve any problem, observing all the while how man continues to treat the earth and its life forms that run, fly, swim, and slither away from him for all their lives are worth – those that aren’t rooted in the ground, unable to move – we can’t help but wonder Who’s Kidding Whom.

Then we go to the natural world, watch, and listen. And it tells us that a Great Storm is rising, and that before long things will become very Interesting – very Interesting, indeed.

We would like to pass along something that we’ve learned directly from the earth, as well as from Taoists, Tibetan Buddhists, Native Americans, the writings of the prophet Isaiah, and others: A new way of life is coming – one so unlike today’s that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to describe in today’s terms. We might call it The Day of Piglet.

But to conclude what we were saying... Whether many people realize it yet of not, man, the Inferior Animal, has by now proved himself incapable of keeping his own species – and others – alive for very much longer. So the earth has begun its own plan to set things right. True to its generous, gentle, and loving spirit, it has been giving us one warning after another of what it will be doing – doing, we wish to emphasize, for the sake of human survival. The sensitive are receiving the messages. But one day when they least expect it, the insensitive will suddenly find themselves Out in the Cold, rather like the mammoths found every now and then up north encased in ice, with once-fresh vegetation in their mouths and an “I say – who just shut off the heat?” look in their eyes. As we understand it, the major cause of What’s Coming is the present-day denuding of our planet – the massive overcutting of its forests.

American citizens are spending one billion tax dollars a year to subsidize the U.S. Forest Service’s Giant Giveaway of old-growth public forests to the logging industry and Japan, causing countless native animals and birds to lose their homes. By now, ninety-six percent of the nation’s original forest has been removed. Meanwhile, the government of China is permanently employing forty-five million people in reforestation, making tree planting a compulsory subject in schools, and decreeing that every Chinese citizen over the age of eleven must plant from three to five trees a year. (The smaller children are being taught to plant grasses and flowers.) Maybe these people Know something.

“Back again, eh? Did you find Pooh?”

“No,” replied Piglet. “I don’t know where he is. Hello, Eeyore.”

“Ah,” said Eeyore. “Friend Piglet. Not like some around here.”

“Eeyore,” said I, “have you seen Pooh?”

“Yes. I have. He’s a rather short, roundish Bear – pleasant personality, but not particularly intelligent, if you know what I –”

“Yes, yes. But do you know where he is?”

“No.”

|

“Oh, here he comes, Piglet – with Rabbit.” “Pooh,” asked Piglet, “did you remember to help Owl remove that –” “Of course,” said Pooh. “I have a phonographic memory, you know.” “You mean,” said Rabbit, “a photographic memory.” |

“So you took care of it,” said Piglet.

“Took care of what?” asked Pooh.

Yes. But let’s continue, shall we? We’d like to suggest a thing or two that might help us through the previously mentioned Approaching Transition.

As we hope we’ve shown by now, Taoism is not an Unbending Path. After all, Taoism follows Tao – and Tao does not operate in a rigid, unyielding manner. As Lao-tse emphatically stated in the first line of the Tao Te Ching, “The Way that can followed [literally: ‘The Way that can be wayed’] is not a changeless way” (a line usually translated as “The Way that can be told is not the Eternal Way”). Traditionally, Taoism is considered the Way of the Dragon – the dragon being the Chinese symbol of transformation. Considering the Bad Press that dragons have received in this part of the world, perhaps a better image would be that of the Butterfly. Whatever the symbol used, Taoism is a Way of Transformation – a way through which something is changed into something else.